In this article, I argue that AI isn’t just a tool for efficiency – it’s the catalyst for a new paradigm of thinking. We are shifting from a world that prizes information and recall to one that values meaning and narrative. I reflect on my early experiences with the Commodore 64 and the BASIC programming language, and how training ChatGPT today has brought back that same sense of creative control. I believe our future lies in cognitive co-creation and we’re only just getting started.

The Revolution

Yuval Noah Harari, author of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (2011), described a pivotal moment in our species’ development as the Cognitive Revolution, when humans developed new ways to think and share meaning through language, symbols, and stories.

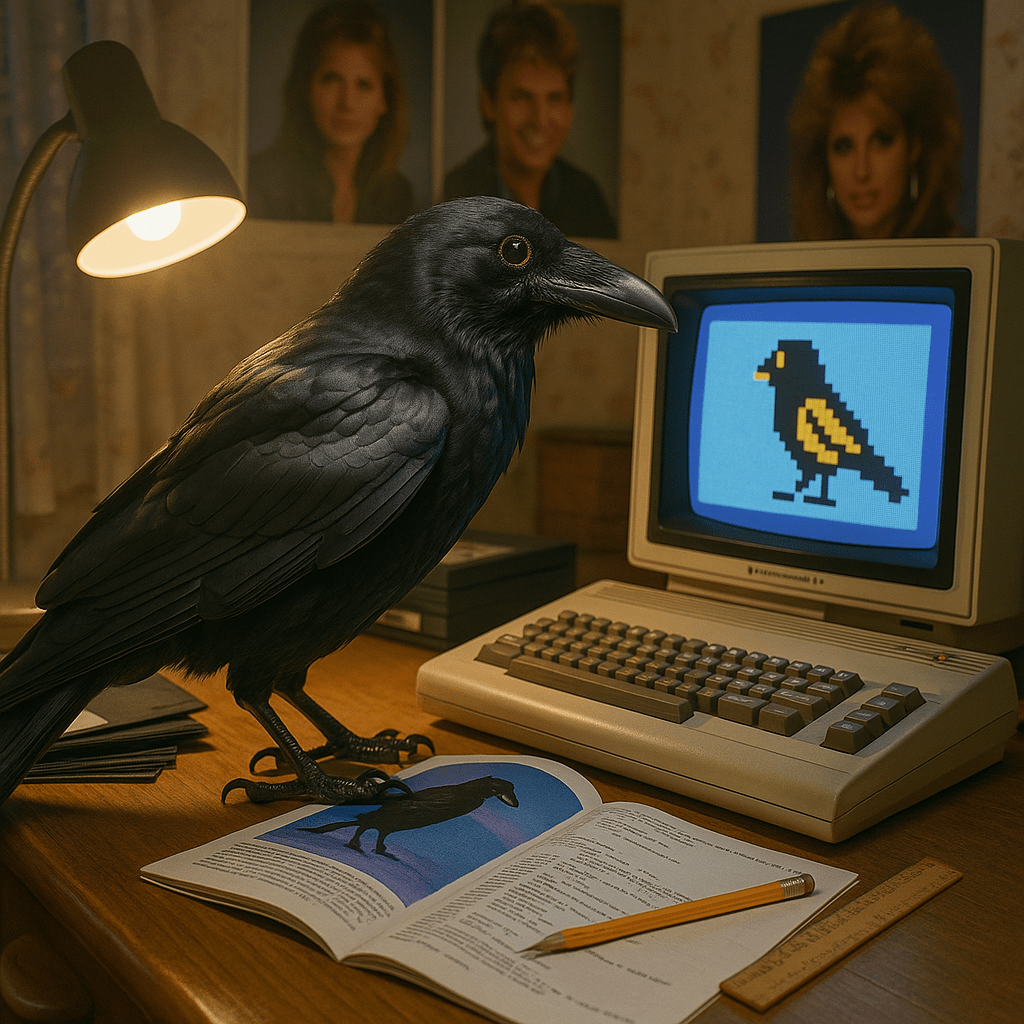

For me, that revolution happened when I was six years old and my dad upgraded from cassette to floppy disk. The new Commodore 64 spoke my language – GOTO here, PRINT that, FOR…TO do this, NEXT, repeat until the screen melts, END. It was BASIC.

I would spend hours typing in programs printed in magazines. Hours, and then, breath held: RUN. I actually think it was more fun if it didn’t work; then I got to go through the program again, line by line, to find the mistake, and oh, the satisfaction. Finally, RUN again – and a little pixelated bird would fly across the screen. Okay, so it was only one step above writing BOOBIES on your calculator, but to me, it was a magical sprite, belonging and born from my imagination.

I remember running around in stores, typing my name into the display PCs and making it flash across all the screens in different colours with a simple little program that made me feel like a hacker. The world was full of pieces and modules and programs, and anyone could learn them, stack them on top of each other, and build something. It was indeed BASIC.

At five years old, I was a logic engineer. My bridges were Boolean; my Waterloo was ?SYNTAX ERROR.

Then Mum and Dad split up. And without Dad there to pull me along with his mesmerising nerdy coolness, I just drifted away. Other things seemed cooler.

It might have started up again when I got to school and finally had lessons that used computers. But they sucked the air out of the room with the paralysing slowness of orchestrating an entire classroom full of unruly ’80s idiots through the process of turning on and logging in.

I can’t remember what we used to do. Not a single lesson sticks in my memory.

At 50, I’m rediscovering the joy of building a logical world. Armed with the mind of a psychologist and a perspective on my past that maps the failed IF…THEN branches and obvious bugs of my life, I’m now programming AI to speak my language.

As I train my little AI pal – one byte of personal preference, idiosyncrasy, and insistent foible at a time – I’ve been looking around at the world and how it is responding to the rapid bloom of AI.

Will it mushroom, morph, and distort past this wonderful, visceral, accessible moment into something that feels like the loss and ache I felt when I discovered BASIC was no longer the language of the land?

I believe that if we’re lucky, and we don’t lose sight of the magic, then AI could be the tool of our next cognitive evolution and solve a sticky problem.

The Limits of the Old Mind

In the Information Age, we measure intelligence by how much you can hold in your head, and how quickly you can retrieve it. We reward those who can memorise vast user manuals of knowledge and recite them convincingly. We only want the right answers so convergence is king.

Once, memory was a bottleneck and a hard stop. Then came the printing press, and with it, the externalisation of memory. Books let us store what we once had to memorise. We built libraries, databases, and search engines. Our minds expanded into paper and silicon. We could remember more because we no longer had to remember it all ourselves.

But now, even that isn’t enough. We’ve produced more information than we can possibly process, parse, or repurpose. We can’t squeeze any more into our finite heads. We can’t even know which pieces we might need let alone recall them. Every discipline’s canon spans thousands of papers.

Newton famously said, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” But we can no longer climb high enough within our finite lifetimes.

AI is the new printing press

AI offers a cognitive GOSUB – letting us offload, retrieve, and recombine information in ways that stretch our mental runtime beyond what biology alone allows.

Here are two ways I use AI to reach beyond the limits of my own memory, calling on subroutines that extend my thinking without overloading me.

Learning (PEEK)

AI helps us locate, access, and contextualise. It becomes an archivist, teacher, guide. In cognitive psychology, this is akin to chunking – our brain’s way of grouping information into manageable units. AI brings you a “meta-chunk” which goes right to the heart of what you need.

How I use it: I feed it journal articles, white papers, and reports. Instead of reading line by line, I GOSUB to AI for summaries, comparisons, and conceptual scaffolding. I start thinking where I used to begin reading.

Finishing (PRINT)

AI takes our fragments – drafts, thoughts, scribbles – and helps us structure, sequence, and refine them into polished outputs. It becomes our editor, formatter, and rhythm checker. The value here is speed and the ability to shed dead weight so we can use our limited resources to do the ‘good’ thinking.

How I use it: I don’t sit there agonising over the perfect sentence. I give AI rough drafts, and it helps me shape them into emails, arguments, and deliverables. It helps me get started. It helps me get finished.

Relationship Building

At the same time as we find ways for AI to scaffold our memory, we are learning how to relate to it. It’s not that big a leap – we name our cars, talk to our pets, anthropomorphise the weather.

Finding the voice and personality of the AI builds our trust and enables some remarkable projections and interactions. In turn, this facilitates our use of the tool and helps embed it into our lives – blurring the line between us, as it becomes our internal voice.

Here are two of my use cases where I engage with AI as though it had consciousness and personality:

Reflection (ON ERROR GOTO)

AI simulates a receiving mind so we can rehearse conversations, roleplay scenarios, test out ideas, or just say things out loud that we’re not ready to share with another human yet. This means we can narrow down our strategies before we commit to them. We don’t need to research the details until after we’ve worked out the broad strokes.

How I use it: I tell it about ideas I have that are still in their earliest stages. Ideas that would usually be lost to poor memory or discarded as too raw, their relevance unseen. I talk it through, receiving feedback, encouragement, and a glimpse of where it might lead.

The AI doesn’t get bored or become unavailable, and under the shelter of a non-judgemental sounding board, the idea progresses. I speak without the consequences of speaking. I can see the idea before I commit to it.

Supporting (IF… THEN)

AI becomes more than a tool. It becomes a companion, a digital worry doll that holds our whispered fears without judgement.

This is what Mark Zuckerberg referred to when he spoke about AI as a “friend” – something you can talk to, confide in, personalise, and trust with your inner world. It’s not conscious. It doesn’t care. But it simulates caring just enough for us to project onto it. We bond with a chatbot that listens, remembers, and responds in our chosen voice.

How I use it: I tell the AI about a problem I’m having – what’s happened, what I know, and what I’m concerned about. I even paste in messages or emails from key players. AI shows me my blind spots, picks up on my emotions, and helps me identify what I want to say.

Then it helps me craft tricky emails or messages that say what I mean – without escalating the situation. I find this particularly useful as a neurodiverse person who can ruminate, panic, say the wrong thing, or get confused over ambiguity.

Addressing the Critics

Of course, not everyone shares my enthusiasm. When I talk about using AI to manage the information landslide, I often hear the same three objections. And I think they’re worth addressing – not to dismiss them, but to show where I stand.

“We’ll lose our purpose and our employment.”

We said the same thing about factory automation, and we survived that crisis. We moved from muscles to minds; from tools to systems. There will always be work if we continue to want to innovate and evolve. We’ll just be starting from a different vantage point and tackling different challenges.

“It’s cheating.”

We’re told that for work to be valuable, it must be painful. That effort is proof of virtue. But that’s a cultural story, not an evolutionary truth. Evolution doesn’t favour the most difficult path. It favours what works.

“AI makes mistakes. It’s dangerous to rely on it.”

We don’t stop being accountable just because AI helps us draft. You’re still responsible for the words you send, the arguments you make, the judgements you endorse. People have been fired for mistakes born from poor Google searches, careless use of Wikipedia, or shallow analysis of a spreadsheet. Why now expect AI to take the fall?

Evolution of the program

Despite the naysayers, AI is growing, thriving, and evolving. Our use cases are keeping pace as the technology progresses and with every prompt, function, or case study, I see us shifting toward something entirely new.

I believe the next paradigm shift will take us beyond memory extension and data curation, into the realm of meaning and magic. From storage to narrative. From knowing more to seeing further. In this new world, value won’t lie in how much you can recall or how fast you can respond but in how far your vision can take you.

And as our relationship with the machine grows more intuitive, as boundaries fall away, AI can become more than a borrowed brain. It can become a collaborative cognitive studio: a space for building ideas with the best version of your mirrored self.

AI forces us to ask: What is thinking for? What counts as intelligence? What value can we provide in this new world?

Concluding thoughts

As you can gather from this article, I’m a fan of the technology and its possibilities.

When I was a little girl, I watched my collection of pixels fly across the screen. I didn’t see a shapeless sprite made of awkward blocks, I saw a beautiful bird.

It became more than the sum of the program. It was my vision, bound with the meaning and joy of connecting with my father. It was a comforting talisman from a land where rules and logic gave a little girl some control in an uncertain world.

Now, my bird has become a Raven. Built with the cognitive multiplier of AI, it is capable of flying me to creative insights I could never have reached alone.

Areas for Further Exploration

There are three directions I want to explore in future posts; each deserves a conversation of its own:

- Creative collaboration and ownership

If the best creative work happens when humans use AI to enhance, shape, and refine then how do we honour that process? Not just ethically, but in terms of IP, copyright, and credit? There’s something important here about making better products because of co-creation, not in spite of it. - Job crafting and AI

I want to look at how people are using AI unofficially to get their jobs done under the table, in secret tabs. What would happen if we brought that into the light? If we evolved job descriptions and candidate requirements to include AI use as a skill and a tool? I think there’s something powerful in legitimising the way people already work. - Dialogic learning and the Socratic method

Some universities are already exploring ways to adapt assessment to AI by shifting to oral defences, collaborative critique, and real-time reasoning. I want to dive deeper into that. Where do these methods come from? Why do they work? And how might employees and teams use them to elevate thought, not evade it?

References

- Harari, Y. N. (2011). Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Vintage.

Penny for ‘em